Did you know you’re suppose to actually investigate a genealogical source before you use it?

An often overlooked tool by beginners in genealogy – is the investigation of a source they’re attaching to a record. We could blame it on the “shaking leaf syndrome” that Ancestry has introduced into the genealogical community, but that would be unfair. This issue has been around for centuries. But the new shaking leaf, along with the marketing behind it, facilitates sloppy genealogy, where researchers, generally interested in their family tree, are duped into thinking clicking on a shaking leaf is all there is to doing genealogical research. Before you click on the next “Yes” question posed by Ancestry, remind yourself this, have you actually researched the source you’re about to attach? I’m not talking about checking the veracity of the facts or events tied to the source… I’m not talking about insuring that you’re actually adding an event into your ancestors life that they took part in… those are both vitally important; but so isn’t spending a few minutes of time to research where a source originated from, and what type of information you can glean from it. This information is not only important in placing a score on your record analysis but also in hinting at possible other avenues of research later.

My analysis of sources is based loosely on the standards employed by professional genealogists:

In order to maximize our understanding of the substance and reliability of any record, we must first understand that record within the context of its source. [1]Anderson, Robert Charles, FASG. Elements of Genealogical Analysis, p. 2. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014.

Charles Anderson reports in Elements of Genealogical Analysis that there are four basic questions we should address to any source [2]Anderson, Robert Charles, FASG. Elements of Genealogical Analysis, p. 3-22. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014.:

- Is it the original or a copy?

- When was the source created?

- Who created the source?

- What formulae were used in creating the source?

For my own purpose, I have adopted his four basic questions, expanding one, changing the wording of one, adding a fifth, and hopefully structuring them to make them a little easier to remember:

- Who created the source?

- What template was used in creating the source?

- When was the source created?

- Where has that source been located since it’s creation and is it the original or a copy?

- Why or how is this source important to my research goal?

In my investigations I answer each of these five questions for each of the sources I research, but the Why is really independent on each of our own goals, so I will simply reflect why or how that source is important in my research at that moment.

Who created the source?

When evaluating a source you need to know who created it. Identifying the creator of the source enables you to value the reliability and originality of the source. For instance, did the census taker follow the instructions for that census? If he did you may consider valuing the reliability of that source greater then you would for a census taker who did not appear to follow the instructions. The same may follow with a town or county clerk. A set of records for a community was likely created by different town clerks over time and each town clerk brings to the task of recording these records their own peculiarities, handwriting, record-keeping and general knowledge of the town happenings. You may find when reviewing the overall records that one town clerk paid better attention to accuracy in their reporting then others, and should consider that in your overall value of reliability for the source.

What template was used in creating the source?

Most genealogists are familiar with blank census forms. I find them invaluable when trying to determine the earlier census (1800-1840) columns when looking at surviving images of those census. In a lot of records we consult in our genealogical research, an actual template was used by the person recording the event, this especially holds true in Government records. Sometimes though, there were no physical templates but an accepted practice of ordering and/or writing out the event. Charles Anderson describes this as a formulae, [3]Anderson, Robert Charles, FASG. Elements of Genealogical Analysis, p. 17-18. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014. but I’ll keep to the more familiar wording of template. French Canadian Church records are notorious for utilizing a method of recording events where a non French speaker can reasonably interpret the information found in the records (if you can read the handwriting).

When was the original source created?

It’s important that you determine when the original source was created. In valuing the worth of evidence in genealogical research, it is generally accepted that the further away from the original event that the record appears the less likely it is to be reliable. This won’t always hold true, but it’s yet one determination you should be using as you determine the reliability of the facts presented. Christine Rose in Genealogical Proof Standard states the following concerning this “distance in time”:

The weight of a derivative source may have more to do with the type of derivative. A microfilm or photocopy made in 2009 from the 1804 original deed is more credible than a poor handwritten transcription made in 1850 from that 1804 deed, even though the transcription was many years closer to the event. [4]Rose, Christine. Genealogical Proof Standard, p. 6. San Jose California, C.R. Publications, 2014.

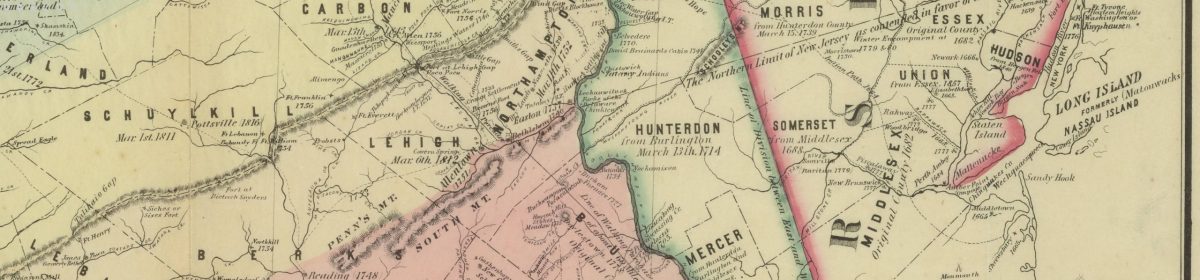

Where has that source been located since it’s creation and is it the original or a copy?

In order to determine the authenticity of a source you need to be able to show the provenance of it. We need to identify the record of ownership of the documents referenced (and often imaged) in the online collection, as well as ownership and creation of the database itself.

After determining when the original source was created, and it’s provenance, determine whether the record you are looking at is in fact the original, or is it a copy of the original? Most online genealogists are not going to handle or view the original documents of an ancestor, but we will often view a photographic image of the original document that somebody else made. Professional and amateur genealogists often handle the determination of this as a copy or an original differently. It is in fact a copy. But in value it sits directly beneath, only the original, and since you or anyone else are likely to never see the original, it as a copy, is probably the most reliable record you will find.

Why or how is this source important to my research goal?

My final step in source analysis is to determine why or how this source is needed to resolve the particular research goal I am trying to achieve. Some may find this an interesting choice when valuing the reliability of a record, but I’ve found as I research that I need to place some weight on my personal needs and my likely ability to find further evidence. While I recognize that genealogists are supposed to collect all information potentially relevant to the questions they investigate, sometimes, whether for financial reasons or reasons of time, this just isn’t possible.

If you’re interested in what professional genealogists have to say about a “reasonably exhaustive search” then Judy Kellar in two of her 10-Minute Methodology blog posts delves into this and does a thorough enough job, that I’ll just refer you to both of her posts. The first deals with what Is “Reasonably Exhaustive” while the second attempts to answer, how do you know you’ve reached what is considered reasonably exhaustive?

- 10-Minute Methodology: What Is “Reasonably Exhaustive” Research?

- 10-Minute Methodology: “Reasonably Exhaustive” — How Do We Know We’re There?

When I look at the source’s importance in helping me resolve my research goal, I am merely equating it to the overall number of records available in a reasonably exhaustive research for that record type. Irregardless of whether my “reasonably exhaustive” search is what you consider reasonably exhaustive, I will insure that you know exactly the searches I made, the records I found, and how I determined which source was likely more valid.

Conclusion

Source analysis is an important step in the genealogical research. While it’s often the first thing discussed by professional genealogists, it’s almost always the last thing amateur genealogists perform. It’s usually left for the time when a researcher, suffering from the effects of the “shaking leaf syndrome,” realize that they’ve attached all these people to their family tree, and all these events to those people, yet some of the facts and events of their ancestors lives simply don’t add up. And then they begin to doubt whether a person in their tree really is an ancestor. Don’t wait for that time… begin now, at the start of 2016, to first analyze a source before you use it.

References

| ↑1 | Anderson, Robert Charles, FASG. Elements of Genealogical Analysis, p. 2. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Anderson, Robert Charles, FASG. Elements of Genealogical Analysis, p. 3-22. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014. |

| ↑3 | Anderson, Robert Charles, FASG. Elements of Genealogical Analysis, p. 17-18. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014. |

| ↑4 | Rose, Christine. Genealogical Proof Standard, p. 6. San Jose California, C.R. Publications, 2014. |